Uprising: The Struggle for the Global Commons

Published in the Spring 2013 edition of Strike! Magazine - a gutsy, innovative newsmagazine which you can buy for just 1 quid.

The last half decade has seen the persistence of social

protests in various forms, including civil disobedience and mass demonstrations.

From the Occupy movement across the Western world, to the Arab Spring in the

Middle East and North Africa; from riots in European capitals, to the current

protests in Cyprus: uprisings have become a regular feature of life.

With the world reeling under the impact of banking

collapses, austerity, environmental crisis, energy woes and rocketing food

prices, it's no wonder that people everywhere are rising up demanding change.

But at the heart of these disparate uprisings is a single

global struggle - a struggle between the people and profit, for access to the

planet's precious land, water, energy, raw materials and resources: a struggle

for the global commons.

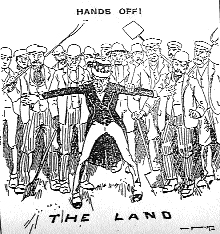

Over three hundred years ago, the struggle kicked off in a

major way when the seeds

of English capitalism were planted amidst mass evictions of peasants from

public lands. Formerly landed peasants, who were compelled by threat of force

to pay tribute, a percentage of their produce, to local lords, now ended up as

a new, landless proletariat. They had no choice but to sell their labour power

for wages to the lords who now owned and controlled what was once their land.

This process of enclosure gradually enforced a new social condition - the

dispossession of people from access to the sources, means and technologies of production

- that was and remains the fundamental basis of modern capitalism.

But in 1649, Gerrard Winstanley

gathered together fifty odd supporters to challenge the new order with a

radical message - to make "the Earth a common treasury for all…

not one lording over another, but all looking upon each other as

equals in the creation". Occupying vacant and public lands

in Surrey, Buckinghamshire, Kent, and Northamptonshire,

Winstanley's rag-tag movement of "Diggers" uprooted the centralisation

of economic power with a call for equal access for all, growing their own food,

and distributing it to the public for free - until local landowners hired thugs

and mercenaries to force them out. Although the Diggers turned to the

government for support, they were ignored and forced to disband.

But the struggle for the 'global commons' had only just

begun. Fast forward to the 21st century, and despite the wonders of modern

industry and global communications, in many ways little has changed. In

countless communities around the world, in the UK, in Spain, in Greece, in

Africa, Latin America and India, the spirit of the "Diggers" lives on

as poor people, farmers, workers, and peasants find themselves making a last

stand between the common land they own collectively, and global corporations in

pursuit of ever greater profits.

Ultimately what we are facing is a struggle between two

visions of the world. Global civilizational crises of climate change, energy

depletion, food scarcity, economic meltdown, and violent conflict, are interconnected

symptoms of a protracted collapse process of the broken, neoliberal model. As

this model increasingly crumbles under the weight of its own sustainability,

the battle for new, more viable alternatives intensifies.

At stake is a new, emerging

paradigm of civilization based on a vision of a global

commons for all - new only in the sense that such a notion has never been

practiced before on a global scale, for it is rooted in ideas and norms that

traditional peoples all over the world have implemented in different ways.

Currently, at the core of our current civilizational model

is a dramatic inequality in access to the Earth's resources, coupled with an

ideology which sees those resources as nothing more than a playing field for a

minority of members of the human species to accumulate material wealth without

limits. The vast majority of the world's resources - not just monetary wealth,

but land, resources and raw materials - is owned and controlled by a tiny

minority of states, monarchs, aristocratic families, banks and corporations.

It is no accident that the Queen

of England - arguably the harbinger of contemporary global capitalism

before its supersession by the United States - is the world's largest landlord,

owning about 6.6 billion acres of land. That is one-sixth of the Earth's land

surface. It gets worse. 1,318

corporations own 80 per cent of the world's wealth, and out of that, a tiny

interlocking nexus of 147 'super corporations' own half of that.

And as civilizational crises deepen, the response of this

nexus of power has been to attempt to increasingly centralise its control of

the Earth's last remaining untapped resources. Indeed, in the last half decade

alone, land grabs largely in the less developed countries have

accelerated dramatically. In 2008-2009, about 22 million hectares were

subject to acquisition according to the World Bank, rising to about 80 million

in 2011. Overall, the last decade has seen a total of 203 million hectares

acquired or being negotiated. This process, driven by varying combinations of

political patronage, violence, and market forces, is leading to the escalating

displacement of poor people from commonly owned lands, and the transfer of

their land into centralised ownership of foreign corporations and investors.

What is driving this process? Short answer: a civilization

in overshoot. Across the board, as resources

are depleting, scarcity is increasing, and prices are rising. Since 2005,

the world food price index has doubled, and despite stabilising this year, remain

at record levels. Simultaneously, the global oil index in the same period has

roughly tripled, and despite promises about shale gas and fracking, even the

International Energy Agency concedes that the age of cheap oil is well and

truly over. Other commodities are also rocketing in value, from metals, to

timber, to chemicals, with one study by Inverto AG noting a "systematic

shortage" leading to "supply bottlenecks", leading companies to

raise prices, passing costs onto consumers.

Unfortunately, even those who claim to be at the vanguard of

responding to these crises can be part of the problem. Chris Martenson, for

instance - a former executive of the giant pharmaceutical firm Pfizer and an ex

Vice President at US defence conglomerate, Science Applications International

Corporation (SAIC) - who now devotes all his time to writing presciently about

the "triple crisis" of environmental, energy and economic collapse,

has very few

meaningful solutions.

Instead of advocating systemic transformation, or

challenging capitalism in its current form, he advocates - effectively - a

strengthening of the most regressive neoliberal principles: Individuals should

seek "resilience" by investing what

remains of their wealth in high value stocks and shares - largely commodities

like farming land, and others which we have seen are rocketing in price - based

on Martenson's strategic investment advice. This sort of 'elitist survivalism'

is ultimately part of the problem: encouraging those with capital to maximise

their control of the world's wealth, as crises kick in, in order to remain safe

amidst imminent civilizational collapse. Meanwhile, the rest of the world's

population can go to hell in a handbasket.

As the persistence of uprisings proves, of course, it won't

work - people will not simply lay back while power seals its destruction of the

Earth.

And civilization is unlikely to collapse so imminently. Despite

that, while things will get worse before they get better, the trends we are

seeing today are illustrative of a fundamental and often forgotten reality: that the 21st

century signals the unequivocal demise of the carbon age. The failure

to come to terms with this fact and its implications is symptomatic of the

delusion of our current era. Whatever happens, by the end of this century (if

not far earlier), our civilization in

its current form will not, cannot

exist. We will either have overshot, drastically and fatally, with horrifying

consequences for humanity, or we will have transitioned to something far more

in parity with our environment - or somewhere in between.

That is why, the choices we make now, the struggles we

choose to partake in now, will be critical in determining the course of our

future. We do not have the option of pessimism and fatalism. There's enough of that

to go around. Our task is to work together to co-create viable visions for what

could be, and to start building those visions now, from the ground up.